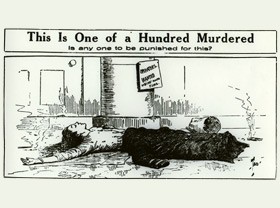

147 Dead, Nobody Guilty

Literary Digest, January 6, 1912. p. 6.

Nine months ago 147 persons, chiefly young women and girls, were killed by a fire in the factory of the Triangle Waist Company at Washington Place and Greene Street, of New York. All of the subsequent evidence, as well as the facts of the tragedy, convinced that New York papers that this factory where hundreds of girls were compelled by circumstances to work for their livings was a veritable fire-trap, though not worse, perhaps, than hundreds of buildings in the city. Last week, Issac Harris and Max Blanck, owners of the Triangle Company, under trial for manslaughter in the first or second degree, were acquitted by a New York jury on their third ballot, after being out an hour and forty-five minutes. While the press in the main seem inclined to accept the verdict itself without serious challenge, many papers are gravely troubled over its practical implication that no one is responsible for that wholesale slaughter, and the feeling is widely exprest that, whatever the explanation of the outcome, justice has in fact been balked. It is "one of the disheartening failures of justice which are all too common in this country," declares the New York Tribune, which goes to say:

The point of view of those who must day after day submit themselves to risks similar to those which obtained in the Triangle factory in thus voiced by the New York Call (Socialist):

There are no guilty. There are only the dead, and the authorities will forget the case as speedily as possible.

Capital can commit no crime when it is in pursuit of profits.

Of course, it is well known that those who were killed in the Triangle disaster are only part, and a small part, of those murdered in industry during the passing year. There are only 147 incinerated and mangled. But there were thousands of others who met a similarly agonizing fate during this year of 1911.

The whole capitalist system is based upon such unspeakable systematic murder, and those who defend the capitalist system defend those murders.

Perhaps the men on the jury had no thought of condoning murder, but that is what they did. They freed of the punishment legal guilt might bring two men who profited by the conditions that made such a disaster inevitable. They did it because they recognized the basic fact that their own interests were in involved in such an action. They stood by their fellow manufacturers and set them free.

But the verdict of the jury in this case by no means settles it. There is another jury that considers the matter, and it is not made up alone of stricken relatives of the murdered women. It is made up of the entire working class. For that horrible murder in the Asch building was one that concerned the whole working class because it was typical of the conditions under which they must gain their daily bread.

And the verdict of the great jury undoubtedly is that not only are Harris and Blanck guilty, but that the whole class to which they belong is guilty, and is foul with the blood of the workers.

It was a fair trial, says the New York Sun, and the New York Herald agrees that the verdict is not surprising, in view of the contradictory evidence presented. The Brooklyn Eagle sees in the result of vindication of the principle of the jury trial, and the New York Press can not regard the acquittal of the Triangle owners as a miscarriage of justice. Says the Press:

The blood of those victims was on more than two heads; on more than twenty heads, perhaps on more than a million heads. Everybody connected with the actual neglect of the fire and building laws, whether in an official or unofficial capacity, shared in the blame.

It was a blind passion for revenge, and not a sound conviction that these men were exclusively responsible for the sacrifice of those lives, that inspired clamor by a large body of the community for their punishment.

Nevertheless one of the jurors has since declared that after this I have no faith in jury trials, and another announced through the press: I know I didn't do my duty to the people, but the court's charge prevented. The point in Judge Crain's charge, to the jury here referred to related to the locking of the Washington Place door on the ninth floor, where dozens of the victims met their death. Said Judge Crain:

Because they are charged with a felony, I charge you that before you find these defendants guilty of manslaughter in the first degree, you must find this door was locked. If it was locked and locked with the knowledge of the defendants, you must also find beyond a reasonable doubt that such locking caused the death of Margaret Schwartz. If these men were charged with a misdemeanor I might charge you that they need have no knowledge that the door was locked, but I think that in this case it is proper for me to charge that they must have personal knowledge of the fact that it was locked.

The juror whose conscience now troubles him is Victor Steinman. To a reporter from the New York Evening Mail he said:

I believed that the Washington Place door, on which the district-attorney said the whole case hinged, was locked at the time of the fire. But I could not make myself feel certain that Harris and Blanck knew that it was locked. And so, because the judge had charged us that we could not find them guilty unless we believed that they knew the door was locked then, I did not know what to do.

It would have been a much easier for me if the State factory inspectors instead of Harris and Blanck had been on trial. For there would have been no doubt in my mind then as to how to vote.

Their duties are clearly outlined by the law. It was up to them, more than to Harris and Blanck, to see that the door was not locked. But they were not on trial. Yet all the time I was refusing to vote I kept thinking about them.

Asked why he could not feel beyond a reasonable doubt that the owners knew the door was to be locked, Mr. Steinman answered:

Because the evidence was so conflicting and because so many of the witnesses on each side were lying. They told their stories like parrots, and I could not believe them.

All I felt sure of was that the door had been locked. I believed that piece of charred wood and the lock with the shot bolt that the State put into evidence. But then I believed also the testimony that the key was usually in the door and that it was tied to it with a piece of string.

So there was the thought in my mind that during the first rush for the door some panic-stricken girl might have turned the key in an effort to open it. And if that was so, then Harris and Blanck could not have known of it, as the judge demanded they should, to be convicted.

A number of other manslaughter indictments are still pending against Harris and Blanck, altho there seems to be some doubt as to whether they will ever be brought to trial on them. The case which has resulted in their acquittal was regarded as the strongest of all cases against them.